2025 Week 49

Last week, we reported on the landmark Amgen v. Sanofi / Regeneron and Edwards v. Meril 25 November 2025 decisions from the UPC Court of Appeal (CoA), which together set out the definitive test for inventive step at the UPC.

We are now seeing first instance decisions issuing that take those CoA decisions into account. So here we report on three of these – two were found inventive and one obvious. Bear in mind that in all of these cases, the oral hearings took place well before the CoA decisions were issued and it is possible that the first instance decisions were at least initially drafted without the full CoA reasoning being known.

Recap on CoA framework for assessing inventive step

The CoA decisions set out their approach to inventive step in a relatively wordy way. Nothing should substitute going back to the source text of the decisions to understand the CoA approach fully. But if you strip it back, there are basically three parts to the test, with lots of guidance to provide colour for their application. Our abbreviated version for these steps is set out below, with some additional guidance points set out to assist the final step.

1. Establish the objective problem. Be holistic. What does the invention add to the state of the art? The objective problem should not contain pointers to the claimed solution.

2. Find a realistic starting point in the relevant field of technology. There can be more than one realistic starting point.

3. Starting from the realistic starting point and wishing to solve the objective problem, would the skilled person have arrived at the claimed solution?

a. The skilled person has no inventive skills and no imagination.

b. The skilled person requires a pointer or motivation that directs them to implement a next step in the direction of the claimed invention from the realistic starting point.

c. A claimed solution is obvious when the skilled person would take the next step and arrive at the claimed solution:

i. prompted by the pointer or as a matter of routine and/or

ii. in expectation of finding an envisaged solution to the technical problem, when the results of the next step were clearly predictable or where there was a reasonable expectation of success.

d. A non-obvious alternative to solutions known in the prior art can be inventive. An improvement is not required.

In Amgen, the claims were inventive because the skilled person did not have a reasonable expectation of success to take the required next step from the realistic starting point, to reach the invention.

In Edwards, inventive step was found to be present because there was no motivation for the skilled person to make the required changes to the different realistic starting points considered, whether or not the claimed invention provided an improvement over the prior art.

Pari Pharma v. Philips

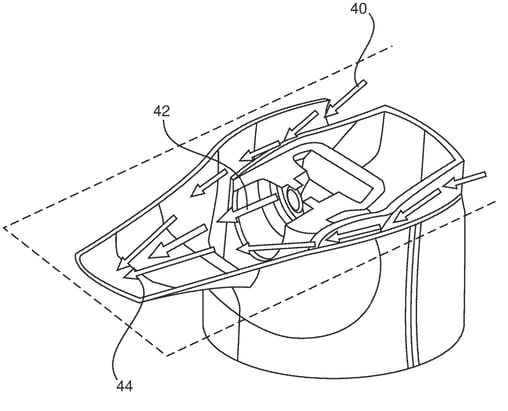

The Milan Central Division issued its decision in Pari Pharma v. Philips on 27 November 2025. Pari Pharma had applied to revoke EP 3397329 B1, which claims a head of a nebulizer for providing an aerosol. The embodiment shown in the drawing below shows the air flow during inhalation, with inlet air 40 coming through back side opening, aerosol droplets 42 being generated and air flowing around the aerosol generator and out of the mouthpiece at 44.

Various issues were aired, but we will concentrate on inventive step here.

Even before interpreting the claims or considering the prior art in evidence, the court started its substantive analysis by first identifying the objective problem that the patent seeks to address. The objective problem was formulated as:

providing a nebulizer head with an improved air-flow guidance, where care is taken that the drug medication does not get on the face of a patient, an improved mixture is provided and re-deposition of drugs onto the aperture surface is reduced.

This objective problem maps closely onto the discussion of disadvantageous aspects of the prior art in paragraph [0002] and the explicitly stated aims in paragraphs [0006] to [0009] of the patent.

The statement of the objective problem follows the CoA’s requirement that the objective problem must be firmly rooted in the patent’s own context and technical contribution, rather than being reconstructed with hindsight or abstracted away from the actual disclosure. It is also interesting to note the technical specificity with which the court articulated the objective problem. Given that the outcome of the inventive step assessment was that the claims are inventive, perhaps there are no objectionable pointers to the claimed solution here. In fact, the detail in the objective problem may have helped the patentee. But if the outcome had been different, the patentee may have had a concern about the formulation of the objective problem.

The court found claim 1 as granted to lack novelty over a novelty-only prior art document. So the court turned to the admissible auxiliary request, which added many features to claim 1 as granted. The objective problem was not reformulated or reconsidered in any way in view of the amendments made in the auxiliary request. This underscores the holistic nature of the establishment of the objective problem.

The court considered several realistic starting points. These included an alleged prior use of the ‘Pari eMotion’ device and various documentary prior art references.

For each starting point, the court asked whether the skilled person would (not just could) have been motivated to combine the teachings, and whether, on making such a combination, they would have resulting in a product in line with amended claim 1. For many of the attacks, this turned on considering different starting points combined with the same secondary reference (D5). A particularly interesting aspect of the court’s reasoning was its consideration of ‘motivation to combine’. D5 related to a nebulizer for a ventilation machine rather than a hand-held nebulizer. The court found that the skilled person would simply not have consulted D5, recognizing that ventilation machine nebulizers have fundamentally different requirements from hand-held nebulizers. Most notably, ventilation machine nebulizers do not need to prevent medication from contacting the patient’s face, as exhaled air is vented away via tubing. The court found that the skilled person would therefore not look to this field as relevant to the objective problem addressed by the patent in suit.

The court also addressed the role of common general knowledge (CGK) in the inventive step analysis. It pointed out that the existence and content of CGK at the priority date must be established by evidence, and the burden of proof lies with the party invoking it. In this case, the claimant had not explicitly substantiated the relevant CGK, and the court found no evidence that CGK would provide the necessary motivation to arrive at the claimed invention.

The outcome was that the amended claims were inventive over all the prior art combinations considered by the court.

JingAo Solar v. Chint New Energy

JingAo Solar v. Chint New Energy is a 28 November 2025 decision of the Munich Local Division in an infringement action with a revocation counterclaim. The inventive step assessment also explicitly followed the CoA framework from Amgen and Edwards.

The patent is EP 2787541 B1, which was opposed at the EPO but the opposition division decided that the independent claims were valid. The defendant was an intervener in the EPO opposition, but the opponents and interveners have now withdrawn their appeals against the opposition division decision.

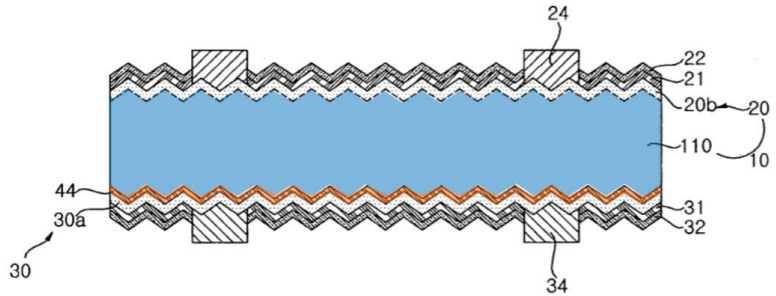

The patent defines a solar cell based on single crystal silicon. A key feature of claim 1 is a tunnelling layer (44 – orange in the drawing below) formed on the entire back surface of the silicon substrate (110 – blue in the drawing below) and a back surface field area (30) is formed on the tunnelling layer.

The defendants raised many different document combinations to attack the patent, but the court persuaded them to reduce this down to five “most promising” attacks. In the decision, the court rejected some attacks as including late-file documents or arguments. It was interesting that some attacks were rejected as late-filed even though they were based on documents that had been introduced into the proceedings on time.

The patent itself defines its objective broadly as:

providing a solar cell which is capable of maximizing efficiency.

One starting point considered by the court was document D22, and the difference between this and claim 1 was the presence of the tunnelling layer. Secondary reference D6 showed a tunnelling layer. The defendant’s argument was that there was no special technical effect associated in the patent with the tunnelling layer. The court was persuaded that D22 teaches away from the invention by requiring direct contact between the back surface of the silicon substrate and the back surface field area.

More generally, it is notable from all the obviousness attacks assessed by the court is that they wanted to be shown clear motivation for the skilled person to modify any realistic starting point towards the invention, even if there is no clear technical advantage provided by the claimed invention.

The patent was held to be valid and infringed.

Decathlon v. OWIM

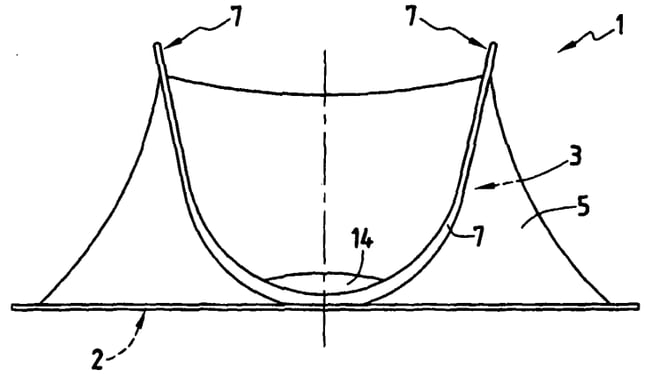

Decathlon v. OWIM is a 3 December 2025 decision of the Mannheim Local Division for infringement of EP 1697604 B1 with a counterclaim for revocation. The patent claims a self-deploying tent (1) with a roof sheet (5) and an inner chamber. The self-deployment comes from the tent having springy hoops (top hoop 3 and base hoop 2) to define the roof and the base. The inner chamber (not shown in the drawing below) is also attached to the top hoop (3) and the base hoop (2), by flexible spacers.

The patent had been opposed at the EPO, but the EPO Board of Appeal (BoA) rejected the opposition. The patent and a related utility model had also been the subject of national litigation in France and Germany, with the courts holding that the patent and the utility model were valid.

The outcome at the UPC was the opposite of the outcome at the EPO and in the national litigation, and based on the same prior art. The court decided that the claims were obvious. The key prior art documents were document DN1 (US 3960161 A – document E10 in the EPO opposition) and document DN6 (US 4858634 A – document E2 in the EPO opposition).

The court noted the specific object proposed by the patent, with reference to the additional steps needed to fit the inner chamber inside a self-deploying single wall tent:

The object of the present invention is to mitigate that drawback by proposing a self-deployable tent provided with an inside chamber that does not require such handling operations.

In case this might be seen as containing pointers to the claimed solution, the court set out various other potential options for the objective problem that were more general in nature.

DN1 was a realistic starting point – it disclosed a tent with an inner chamber, and the tent had a roof hoop but no base hoop. This made it slightly closer than the prior art acknowledged in the patent. But the lack of a base hoop meant that the base needs to be pulled out to apply suitable tension across the whole roof sheet. The court then settled on the objective technical problem:

Based on the content of document DN1, the skilled person recognises the disadvantages of the merely partially self-deploying tent disclosed therein, which still requires manual operations by the user after deployment of the upper part of the tent. This prompts the skilled person to seek improvements to eliminate these disadvantages.

DN6 disclosed a single-wall tent but with the required roof hoop and base hoop, together providing the full self-deployment functionality for the tent. The court were satisfied that the skilled person would be motivated to consider this, when starting from DN1. The EPO BoA had also considered the combination these documents, but had concluded that the teachings of the two documents were not compatible because the skilled person would need to use an inventive step to work out how to attach the inner chamber of DN1 (E10) to the hoops of DN6 (E2).

The court noted the reasoning of the EPO BoA and specifically disagreed. They took a different view of the disclosure of DN6, concentrating not on the words used in the description and claims of DN6, but on what was shown in the drawings. The result was that they found that the skilled person would have used the base hoop from DN6 to improve the structure of DN1 to avoid the additional steps of tensioning the base part of the tent.

The key difference between the UPC decision and the EPO BoA decision does not really turn on the structure of the inventive step test, but on how the ambiguous disclosure of DN6 should be understood. The EPO focused on the text which stated that the hoops are inside the tent – supporting the roof fabric from the inside, and indeed that view is supported by the drawings generally showing that the sides of the tent bulge outwardly. The UPC focused on a drawing that showed a roof hoop on the outside of the roof fabric, but which seems incompatible with the overall illustrated shape of the tent. If the court is right about the disclosure of DN6, then the outcome that claim 1 is obvious seems reasonable.

This blog was co-authored by Isobel Stone and Matthew Naylor.

Isobel Stone

Isobel is a Partner and Patent Attorney at Mewburn Ellis. She is an accomplished UK and European patent attorney whose technical expertise spans a wide range of technical fields in the mechanical engineering and materials engineering spaces. Her work extends across the full IP lifecycle: she has extensive experience in original drafting and patent prosecution work, as well as a keen interest in opposition and other contentious matters.

Email: isobel.stone@mewburn.com

Matthew is a UPC Representative and European Patent Attorney. He is a Partner and Litigator at Mewburn Ellis. He handles patent and design work in the fields of materials and engineering. His work encompasses drafting, prosecution, opposition, dispute resolution and litigation – all stages of the patent life cycle. Matthew has a degree and PhD in materials science from the University of Oxford. His focus is on helping clients to navigate the opportunities and challenges of the Unified Patent Court.

Email: matthew.naylor@mewburn.com

-1.png?width=100&height=100&name=Isobel%20Stone%20circle%20(1)-1.png)

.png)