2026 Week 7

The supply of consumables for printers and copiers has a lot of baggage in the field of IP, competition law and the space in between. Original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) have a lot to gain by their customers sourcing printing consumables from them, while third parties seek to provide compatible consumables for use in the OEM’s printer/copier.

Canon enforced their unitary patent EP 3686683 B1 against the Katun group of companies at the UPC. The patent had been granted in March 2024, with the UPC infringement action filed in June 2024 and a counterclaim for revocation filed in October 2024. Shortly afterwards, the defendants also filed an opposition at the EPO. The outcome at the EPO was that the opposition was rejected, but the written decision has not yet been issued by the opposition division.

On 11 February 2026, the Düsseldorf Local Division (LD) issued its decision on the merits in Canon v. Katun. The outcome was that the patent as granted is valid and infringed. There are two main groups of issues that we report on here: the way in which the LD interpreted the claim and the suite of remedies obtained by Canon, in the face of resistance from Katun.

Background

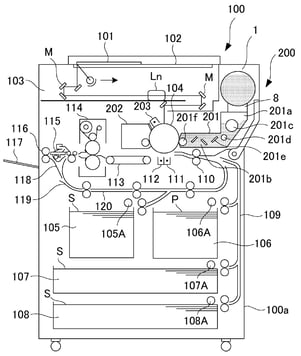

To set the scene, the invention is about getting toner (or “developer” in the wording of the patent) into the right place in printer/copiers of the type used in an office. The toner is provided in a supply container 1 and this whole container is inserted into the printer/copier 100 by the user. There, it interfaces with the internal workings of the printer/copier to ensure a supply of toner for the printing drum 104. The invention is about how the supply container 1 interacts with the receiver apparatus 8 of the printer/copier, with the overall aim of the invention to provide a smoother insertion and connection.

What is the claimed invention?

These types of inventions can be tricky to claim because it is often necessary to specify in the claim how various features interact with external components. That was the case here, with the claim being directed to the “developer supply container (1)”, but needing to define its interaction with the “developer receiving apparatus (8)” (see the top right of the cross-sectional drawing).

Claim 1 is reproduced below, using the feature numbering in the decision. Features that are part of the developer supply container (1) are shown in purple and features that are part of the developer receiving apparatus (8) are shown in pink.

1.1 A developer supply container detachably mountable to a developer receiving apparatus (8) including a developer receiving portion (11) provided with a receiving opening (11a) for receiving a developer, and a supported portion (11b) integrally displaceable with the developer receiving portion (11), said developer supply container (1) comprising:

1.2 a developer accommodating portion (2c) accommodating the developer;

1.3 a discharging portion (700) provided with a discharge opening (3a4) in a bottom side of said discharging portion (700) for discharging the developer accommodated in said developer accommodating portion (2c);

1.4 a supporting portion (30) provided at said discharging portion (700) and capable of supporting the supported portion (11b),

characterised in that

1.5 said supporting portion (30) is movable relative to said discharging portion (700), and in that

1.6 said developer supply container (1) further comprises a moving mechanism (4f, 30b; 30Ca, 30Cb; 60, 61; 70, 71; 90) for moving said supporting portion (30) upwardly relative to said discharging portion (700)

1.6.1 while supporting said supported portion (11b) to move the developer receiving portion(11) toward said developer supply container (1)

1.6.2 so as to bring said receiving opening (11a) into communication with said discharge opening (3a4) with a mounting operation of said developer supply container (1) to the developer receiving apparatus (8).

As you can see, the features of the developer receiving apparatus (8) are critical to understanding the functioning of various features of the developer supply container (1).

It’s also useful to know that claim 17 defines a system with these components present together:

17.A developer supplying system comprising: a developer receiving apparatus (8) including a developer receiving portion (11) provided with a receiving opening (11a) for receiving a developer, and a supported portion (11b) integrally displaceable with the developer receiving portion (11); and

a developer supply container according to any one of claims 1 to 16.

Claim interpretation

The defendants argued that the features of the supply container and the receiving apparatus are so closely interlinked in the claim that the claim should be understood as defining the interaction of these parts. This was key to their defence, because they could then say:

-

Their attacked embodiments did not include the features of the receiving apparatus, because they were dealing only in the supply containers, and so there should be no direct infringement, and

-

Selling the supply containers for use in the printer/copiers should not be considered to be indirect infringement, due to exhaustion of rights.

The court did not agree, and from this point in the case the outlook for the defendants was bleak. This was the key assessment by the LD:

However, the developer receiving apparatus itself, and therefore the printer or parts of it, are not subject of claim 1. Claim 1 only states that the developer supply container is ‘mountable’ to such a developer receiving apparatus. The skilled person will understand this to mean that the parts of the developer receiving apparatus named in feature 1.1 — the developer receiving portion, the receiving opening and the supported portion — are not claimed to be present. The developer supply container only has to be suitable to be detachably mounted on a developer receiving apparatus as described in claim 1.

The court relied on various parts of the description to support this point of view, and also on the fact that claim 17 defines the system, which is presumed to be of different scope to claim 1.

Validity and infringement

The defendants’ arguments for invalidity were based on added matter and prior art. We don’t need to go into them here – they were rejected by the LD.

The defendants’ only arguments for non-infringement were based on their interpretation of the claim to define, in effect, the combination of the supply container and the receiving apparatus. With this interpretation rejected, the court found that the claim 1 was directly infringed.

The court therefore decided not to make any comment about whether there was indirect infringement, i.e. whether there would have been a credible defence of exhaustion of rights.

Remedies

Before we go further, it’s useful to know that, during the dispute, Katun had apparently put up a notice on its US website to this effect:

‘Katun is confident the products it is selling and distributing for use in Canon applications are non-infringing.’

Regular readers of UPC decisions will know that the orders of the court tend to be set out in capital Roman numerals. We’ll follow that approach here, for the most interesting remedies sought by Canon and the defences mounted by Katun.

I. Injunction

Since the court found that there was direct infringement, the scope of the injunction sought was straightforward. While an injunction is not formally automatic at the UPC, it is for the defendant to show why there are special reasons that an injunction would not be appropriate. Katun argued that the exercise of patent rights by Canon was anticompetitive, leading to high prices for consumers. The court dismissed this out of hand.

Secondly, Katun argued that there should be a grace period of six months in which they could sell out their stock. They presented this as the more environmentally sound outcome, being in the public interest for the products to be used rather than destroyed. Again, the court dismissed this argument, in effect blaming the defendants for continuing to manufacture the products despite knowing the risks of patent infringement.

The defendants also argued that the claimant should provide security for enforcement. The court considered that no justification had been provided for this, in particular no explanation as to why Canon would not be able to pay compensation later if the remedies were overturned.

II. Penalty payments for breach of the injunction

These were ordered for each case of violation of the injunction: up to EUR 10,000.00 for each case of violation. Note that this would be payable to the court – the penalty payment is not a damages award.

III. Declaration of infringement

This is self-explanatory.

IV. Provision of information about the extent of infringement

Here the court set out a detailed list of the information to be provided by the defendants.

V. Product recall

This was ordered with a threat of a periodic fine (again, payable to the court) of up to EUR 1,000.00 for each day of delay.

VI. Product destruction

This was also ordered with a threat of a periodic fine of up to EUR 1,000.00 for each day of delay, including the recalled products under V. The defendants argued that this remedy would be disproportionate. In particular, they argued that it would be possible to modify each existing product so that it no longer infringed the patent, and so they should be allowed to do this without destroying the entire product. The court did not agree that this would be appropriate, worrying about the risk of the products being sold and then re-engineered back into infringements.

VII. Damages

This part of the decision was interestingly worded. The court declared that the defendants are obliged to pay damages dating back to the date of grant and also for damages “yet to be incurred”. This apparently sets the scene for damages (perhaps in addition to the penalty payments) for infringement after the date of the decision.

VIII. Interim damages

The defendants were ordered to pay interim damages – not at the level of EUR 400,000 proposed by the claimant, but at the lower level of EUR 100,000. The intention of this amount is to cover the defendant’s anticipated costs for carrying out a formal damages assessment at the UPC, which takes place in a separate procedure.

IX. Publication of the decision by the claimant

The court allowed the claimant to display the decision on its website for one month and to publish it in up to five industry journals.

X. Publication of the decision by the defendants

This was a telling part of the overall decision:

As mentioned before, the Defendants have used their own website to report on the proceedings. They have expressed confidence that there has been no infringement. An obligation to publish the operative part of the Court’s decision stating that an infringement has occurred is an appropriate measure to remove the impression created by the Defendants themselves.

The defendants were therefore ordered to publish the decision on their own websites for 1 month. This was in part due to their own website announcement that they believed there was no infringement.

XI. Costs

The defendants argued that their behaviour should be rewarded in the decision on costs. They explained that the infringement action had been launched on them without advance warning and they had sought in good faith to find a way to settle the proceedings throughout.

The court did not agree, noting that the only way for the defendant to have avoided an adverse costs decision would have been to submit a cease-and-desist declaration at the earliest opportunity, which here would have been at the deadline for filing the defence. Because they chose to fight, they are on the hook for the vast majority of the patentee’s costs.

Overall, the suite of remedies obtained by Canon seems to be just about everything on the menu.

Matthew is a UPC Representative and European Patent Attorney. He is a Partner and Litigator at Mewburn Ellis. He handles patent and design work in the fields of materials and engineering. His work encompasses drafting, prosecution, opposition, dispute resolution and litigation – all stages of the patent life cycle. Matthew has a degree and PhD in materials science from the University of Oxford. His focus is on helping clients to navigate the opportunities and challenges of the Unified Patent Court.

Email: matthew.naylor@mewburn.com