Hilda-Georgina, examines the rulings in Original Beauty Technology & Ors v G4k Fashion Ltd & Ors and Chanel v European Intellectual Property Office and Huawei Technologies Co.Ltd.

In the words of Gabrielle Bonheur “Coco” Chanel, fashion designer and founder of the eponymous and iconic brand, Chanel, “if you want to be original, be ready to be copied.”

Opening remarks on The Legal Runway

Creativity, inspiration, and imitation are all facets of the fashion industry. In this article, “the legal runway” is used to refer to court decisions involving parties in the fashion sector, namely; the fast fashion brands: House of CB and Oh Polly and the luxury fashion maison, Chanel. The rulings in Original Beauty Technology & Ors v G4k Fashion Ltd & Ors and Chanel v European Intellectual Property Office and Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd. will be examined. Weaknesses in legal submissions and the evidence adduced will be explored in this article to help identify tactics that can be deployed to “walk the runway” to success in legal proceedings.

Designs X The Legal Runway

Original Beauty Technology & Ors v G4K Fashion Ltd & Ors

In February 2021, Mr David Stone (sitting as a Deputy Judge of the High Court) handed down a lengthy judgment comprising 513 paragraphs in relation to alleged design rights infringement and passing off of fashion garments spanning tops, dresses, and jumpsuits. The Claimants sell apparel such as bodycon and bandage dresses under the main brand House of CB (formerly Celeb Boutique) and the sister brand Mistress Rocks. A passing off action was also brought against the Defendants who sell apparel under the Oh Polly brand (formerly Polly Couture). The Claimants and Defendants are direct competitors in the fast fashion industry with a social media centric business model “selling celebrity-inspired fashion”1. Beyoncé, Kylie Jenner, and Jennifer Lopez have been photographed in House of CB dresses, whereas Oh Polly is a more recent entrant into the burgeoning fast fashion market and a digital native retailer akin to Fashion Nova and Shein. It was alleged that the Defendants had copied the Claimants’ business model, social media, marketing, packaging, and presentation and consequently consumers were deceived into thinking that the Oh Polly brand was a sister brand to House of CB akin to Mistress Rocks. Thus, constituting a misrepresentation that has caused and is causing damage to the goodwill of House of CB which establishes the tort of passing off.

The Claimants alleged unregistered design rights infringements under the UK and EU regimes in relation to the designs of 91 garments. At a Costs and Case Management Conference (CCMC), each side was directed to select 10 garments so that 20 garments in total would be the subject of a liability trial for infringement and passing off. Mr David Stone explained that the length of his decision reflected the extensive exercise of over 270 comparisons resulting from (a) comparing each of the Claimants’ 20 garment designs against the prior art identified by the Defendants for both the UK and EU regimes for the validity assessment; and (b) comparing each of the Claimants’ 20 garment designs against each of the allegedly infringing garment designs for both the UK and EU regimes for the infringement assessment. Mr David Stone opined that it would have been more efficient and cost effective for the three designs that were representative of the 91 garments at issue in the proceedings to have been selected for trial. The remaining 88 garments could have been disposed of by consent and if mutual agreement could not be reached, the relevant designs could have relisted as garments at issue.

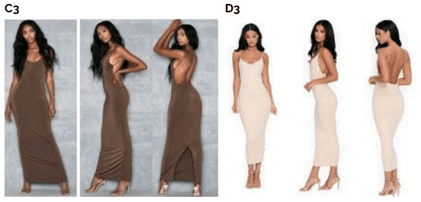

During the course of the trial, the Defendants admitted that it had “referenced” a House of CB or Mistress Rocks garment during the design process of nine out of 20 garments at issue. The selected garments were each given a number, together with the letter “C” to represent the Claimants’ garment in which UK Unregistered Design Rights (UKUDR) and Community Unregistered Design Rights (CUDR) were asserted, or the letter “D” to represent the Defendants’ garment which is alleged to infringe. For example, C3 was sold on the Mistress Rocks website in mocha and red colourways but D3 was never sold in these colourways. Both garments are shown below in Figure 1.

Figure 1

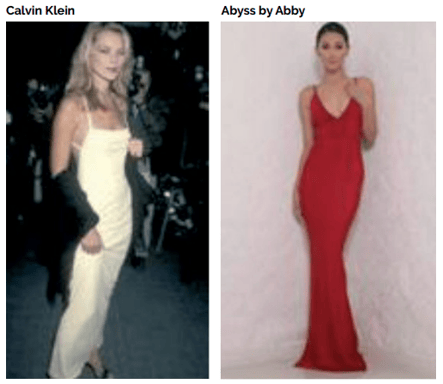

By way of example, the Defendants challenged the validity of the UKUDR and CUDR asserted in C3 by relying upon a Calvin Klein dress in relation to the former right and an Abyss by Abby dress in relation to the latter right. The Calvin Klein dress was worn by the supermodel, Kate Moss at the 1995 Met Gala in homage of the theme “Haute Couture”. The Met Gala which is officially known as the Costume Institute Gala, this is an annual fundraising event for the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan, New York. The theme of the 2021 Met Gala was “In America: A Lexicon of Fashion” and attendees at “fashion’s biggest night of the year”2 included the 2021 US Open Women’s Single Tennis Winner, Emma Raducanu who wore a Chanel ensemble.

The two main prior art designs relied upon by the Defendants in relation to C3 are shown below in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Mr David Stone held that C3 was not slavishly copied from the Calvin Klein dress and C3 created a different overall impression on the informed user as the Abyss by Abby dress. For example, the Calvin Klein dress is a loose-fitting maxi dress in a column fit and the Abyss by Abby dress is a floor-length fishtail dress. In regards to the CUDR, C3 was sold in a deep mocha colourway which is distinct to the red dress. The Claimants were successful in relation to the validity of C3 but Mr David Stone concurred with the Defendants that C3 was a generic style of dress and D3 could be differentiated from C3 in relation to the length of the dress, the absence of a slit at the back, the neckline and the placement of the straps. It was held that D3 did not infringe the UKUKDR because it has not been made exactly or substantially to the design of C3, nor did D3 infringe the CUDR because it does not produce on the informed user the same overall impression. The UKUDR and CUDR infringement claims were unsuccessful in relation to D3.

Overall, it was held that seven out of the nine designs in which the Claimant’s designs were “referenced” by the Second Defendant (the CEO of Oh Polly) had in fact been copied. Conversely, the 20 designs of the Claimants’ that had been selected for the purposes of the trial had not been slavishly copied from third party designs such as garments sold by Cushnie et Ochs, Maison Margiela (formerly Maison Martin Margiela) and Hervé Léger which had been put forward by the Defendants’ as prior art. The Claimants’ unregistered design rights were valid in relation to all 20 design garments, however, 13 of the designs at issue were found not have infringed the Claimants unregistered design rights.

It is noteworthy that the Claimants framed the passing off action as one where the “misrepresentation in issue was that of the defendant being a sister brand of the claimant” i.e. misrepresentation as to trade connection. Typically, a passing off action involves an alleged misrepresentation by the defendant to the public that is likely to lead the public to believe that the goods or services being offered are the goods or services of the claimant; as was the case in the Jif Lemon3 case which sets out the classic trinity of actionable passing off which is goodwill, misrepresentation and damage. The Claimants’ relied upon goodwill in the Business Marketing Style and Get-Up and Mr David Stone identified seven main indicia namely; business model and focus, garment design, locations, themes and styling of photographs, packaging, logos and websites. For example, garments on the respective House of CB and Oh Polly websites were arranged by colour which is unusual for an e-retail website. Mr David Stone also found it unusual that Oh Polly which has headquarters in Glasgow, Scotland used the American English expression “depot” in relation to directing consumers to return garments to a returns “depot”.

Overall, it was held that the evidence adduced did not establish that a substantial number of consumers had been misled or deceived into thinking that Oh Polly is a sister brand or diffusion line of House of CB. Apart from one social media post stating that “oh polly is owned by house of cb”, Mr David Stone considered the remaining evidence to show that consumers had identified similarities between some of the seven indicia relied upon by the Claimants rather than a trade connection between Oh Polly and House of CB. Accordingly, the passing off action was dismissed. However, Mr David Stone was sympathetic to the Claimants’ position and expressed that the “Defendants’ have been able to ride on the coat-tails of the Claimants’ successful business model …[and] they have obtained an advantage by copying a successful competitor.”4

Trademarks X The Legal Runway

Case T-44/20 Chanel v EUIPO and Huawei Technologies Co.Ltd

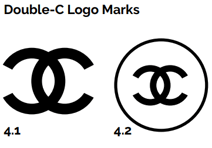

In April 2021, the General Court of the European Union (The General Court) dismissed Chanel’s appeal against the decision of the Board of Appeal of the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO). The intervener, Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd (Huawei) had applied to register a figurative sign at the EUIPO for “two interlocking u-shaped elements in a vertical position surrounded by the basic geometrical shape of a circle”5 in NICE Class 9 (‘the Contested Mark’). The luxury fashion house, Chanel filed a notice of opposition on the basis of two earlier French trademarks for “two bold, black interrupted circles, placed mirror-like and overlapping in a horizontal position”4 for the double C logo of Chanel (‘the Double-C Logo Marks’). The Double-C Logo Mark shown in Figure 4.1 below was registered in NICE Class 9 inter alia in relation to “Cameras, sunglasses, glasses; earphones and headphones; computer hardware’, whereas, the Double-C Logo Mark shown in Figure 4.2 below was registered in NICE Classes 3, 14, 18 and 25 inter alia which Chanel alleged had acquired a reputation in the relevant EU Member State, namely; France pursuant to Article 8(5) of Regulation (EU) 2017/1001.

|

|

| Figure 3 | Figure 4 |

In March 2019, the Opposition Division dismissed Chanel’s opposition against the registration of the Contested Mark in its entirety (‘the Contested Decision’). Chanel had relied upon the relative grounds for refusal for the registration of a European Union trademark pursuant to Article 8(1)(b) and Article 8(5) of the Regulation (EU) 2017/1001 (‘the Regulation’). In the Contested Decision, the Opposition Board held that:

- The Contested Mark was not similar to the Double-C Logo Mark shown in Figure 4.1 above and there did not exist a likelihood of confusion on the part of the public.

- The Contested Mark was different to the alleged reputed Double-C Logo Mark shown in Figure 4.2 above. Therefore, Chanel had failed to satisfy the first condition for earlier trademarks to be granted a broader scope of protection under Article 8(5) of the Regulation.

The General Court upheld the findings of the Board of Appeal that the Contested Mark was visually and conceptually different to the Double-C Logo Marks. The absence of a circle in Figure 4.1 distinguished the earlier mark from the Contested Mark. Even though the Contested Mark and the Double-C Logo Marks were each “composed of two connected elements”7, this did not of itself make the marks similar. Upon closer inspection of the Contested Mark and Figure 4.2, the line where the two curves intersect and form an ellipsis is interrupted in the Contested Mark and the distance between where the curves begin and end in the Contested Mark is also different from the allegedly reputed Double-C Logo Mark. Both the Contested Mark and Figure 4.2 consist of “a circle containing an image referring to stylised letters”8. In the former, it is a stylised letter “h” or two interlaced letters “u”, whereas, in the latter, the stylised letters are two interlaced letters “c” to refer to the “initials of the founder of the applicant company”.9

Closing remarks on The Legal Runway

Intellectual property rights can be strategically leveraged to consolidate market share of a brand; protect creative elements of a brand; enhance the goodwill and reputation of a brand; and generate lucrative revenue streams. The two fashion cases explored in this article give rise to useful practice points on the litigation strategy that can be adopted in intellectual property disputes. Key highlights are summarised below.

- For case management purposes, where there are multiple designs in issue, the parties should endeavour to select a small number of designs which are representative of all the designs subject to the liability trial so as to streamline the proceedings and save the parties both time and expense.

- Whenever possible, judges should be provided with physical examples of garments to facilitate the comparison of similarities and differences which will be helpful during their preparation for the judgment to be handed down. In addition, garments should be provided in “comparable sizes, and comparable colourways.” 10

- The creation of moodboards is a common practice in the fashion industry. If these moodboards are disposed of over time, there is not an obligation on a party to take photographs of moodboards for the purposes of the disclosure/discovery stage in future litigation, in any event, parties to litigation are required to preserve existing documents which should be disclosed if they are relevant to the proceedings.

- Passing off is not a tort of unfair competition and it is actionable only if all three central tenets are present and supported by sufficient evidence.

- Additional damages may be awarded if the defendant(s) adopted a “couldn’t care less” mindset to the rights of other designers and continued “referencing” the claimant(s) designs even after the commencement of legal proceedings.

- The submission that it is permissible for a sign to be compared in a different orientation to which it was applied for, if it aligns with “the perception… the public may have of it when affixed to goods on the market”11 was found to be unpersuasive to The General Court.

- In the determination of whether a mark applied for is identical or similar to an earlier registered trademark, the comparison must be made in the form in which they are registered or as they appear in the trademark application.

Ultimately, the fashion industry is cyclical, fast-paced and competitive which underscores the sentiment expressed by Coco Chanel that “in order to be irreplaceable one must always be different”.

References

- Original Beauty Technology & Ors v G4K Fashion Ltd & Ors [2021] EHWC 294 [426]

- https://www.vogue.com/tag/event/met-gala

- Reckitt and Colman Products Ltd v Borden Inc & Ors [1990] UKHL 12

- Case T-44/20 Chanel v EUIPO and Huawei Technologies Co.Ltd [40]

- ibid [46]

- ibid

- Case T-44/20 Chanel v EUIPO and Huawei Technologies Co.Ltd [39]

- Case T-44/20 Chanel v EUIPO and Huawei Technologies Co.Ltd [39]

- Case T-44/20 Chanel v EUIPO and Huawei Technologies Co.Ltd [40]

- Original Beauty Technology & Ors v G4K Fashion Ltd & Ors [2021] EWHC 294 [13]

- Original Beauty Technology & Ors v G4K Fashion Ltd & Ors [2021] EWHC 294 [20]

This blog was originally published in the The Trade Mark Lawyer, Issue 5 2021 (pages 45 - 50)

This blog was originally written by Hilda-Georgina Kwafo-Akoto.

Karolina is a trade mark attorney and a member of our trade mark team. Karolina's special interest include contentious proceedings, involving trade mark, copyright and design matters. She graduated with LLM in Intellectual Property Law and LLB Law with Another Legal System (Singapore) degrees from University College London. This included a year placement at the National University of Singapore, where she studied Singaporean law.

-1.png)