Throughout the 20th century, plastic has become increasingly prevalent in our everyday lives. To date, it’s estimated that over 8 billion tons of plastic has been produced, with a further 4 billion tons expected before 2050. One culprit is disposable drink bottles, of which we buy around 1,000,000 every minute.

Consumers and companies alike are addicted to the convenience, durability and disposability of plastics, resulting in high worldwide usage. However, the environmental impact is undeniable and unsustainable. Increasing consumer awareness driven, for example, by the ‘Attenborough effect’ has led to a growing market pull for alternatives.

Conventional substitutes like KeepCup® or Tupperware® will always require a degree of preparedness and investment by the consumer. In order to truly replace consumable plastics we need a product that is similarly consumable.

While Attenborough’s Blue Planet II looked at plastic waste in the oceans, others are also looking there for plastic replacements.

In 2013, Skipping Rock Lab first launched ‘Ooho!’; an edible water bottle produced from seaweed. Now, evolutions of the edible membrane are used to package everything from ketchup to cocktails.

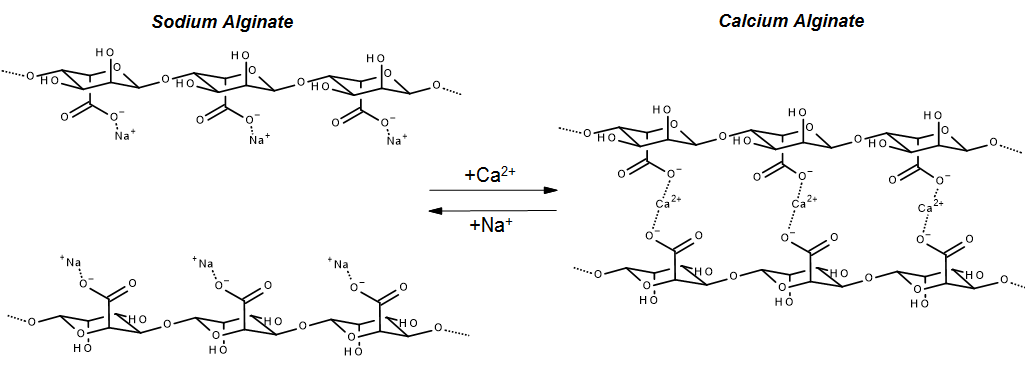

The edible water bottle consists of a biodegradable and food-safe membrane, made from calcium alginate gel. This sugar-like polymer starts life as sodium alginate, extracted from the cell walls of brown seaweed. Treating the sodium alginate with calcium ions results in an ion exchange reaction, where the calcium ions act as cross-linkers between the individual strands of polymer to provide the coagulated calcium alginate gel.

However, this reaction is reversible and the cross-linking calcium ions can be easily re-exchanged for sodium ions (which are abundant in salt water), resulting in decomposition of the polymer. Additionally, unlike traditional plastics where the polymers strands are highly branched, the alginate polymers are unbranched which speeds up the decomposition process. Natural decomposition takes as little as 4 weeks, as opposed to 400 years for traditional plastics.

Given the global use of the plastic bottle, breaking into this market has huge commercial potential. But how can innovators best protect their developments?

Products, uses, or processes can all be patented, provided that the innovation is novel, inventive and industrially applicable.

In this case, the calcium alginate gel itself is a natural product found, for example, in bacterial biofilms. It is also used in wound dressings, thickening agents, and additives for pharmaceuticals and food. Therefore, the calcium alginate gel itself is not novel.

What about the use of the membrane? In fact, this was successfully patented by William Peschardt of Unilever in the 1940s (US 2403547). The patent for ‘artificial edible cherries’ describes their manufacture by spherification.

This technique, now commonly used by chefs, involves dropping globules of sodium alginate solution into a bath of calcium ions. The surface of the globule reacts with the calcium ions to form a thin calcium alginate membrane, which encapsulates the globule.

As a result, the use of the membrane is also not novel. However, the spherification process is restricted to small, caviar-sized globules, so is not suitable for encapsulating larger volumes of liquid required for a drink bottle.

As a result, Skipping Rock Lab have been able to focus their patent protection strategy on the process of manufacturing their edible water bottles. Their published application (WO 2018/172781) describes a process for extruding a thickened sodium alginate gel into a tube. The tubular membrane is simultaneously filled with liquid and sprayed with calcium ions to cross-link the alginate polymer. Finally, pinching the filled tube along its length compartmentalises it into smaller, water bottle sized sacks.

Even in a crowded sector where obtaining IP protection may seem challenging, the value of patenting a new product, use or process should not be underestimated. Obtaining optimal patent protection for any such product, use or process allows inventors to realise the value of their innovation; driving their research forward and bringing us closer to a plastic-free future.

Mewburn Ellis have a long history of working with innovators across the whole spectrum of polymer technology. Our highly skilled and technically diverse chemistry team are well-placed to provide expert advice on how IP can be used to drive new, environmentally friendly, plastics towards commercial success.

Niles is a Patent Attorney working in the chemistry field. Niles has an MChem degree in chemistry from the University of Oxford. His undergraduate research project was on the synthesis of novel perylene diimide containing macrocycles for anion recognition and sensing applications.

Email: niles.beadman@mewburn.com

-2.png)

-Jan-30-2026-12-39-31-4854-PM.png)