Case - T2541/11

This decision provides guidance and clarification in three key areas of EP law:

- it explains when amendments based only on the drawings may be allowable under Art. 123(2) EPC;

- it helped to clarify what is considered to be an implicit disclosure in a patent application; this is important not only in the assessment of novelty but also of “added subject-matter” under Art. 123(2) EPC; and

- it provides guidance on when late-filed documents may not be admitted to the proceedings under Art. 114(2) EPC, and why this is not a violation of the party’s right to be heard under Art. 113(1) EPC by a failure to consider evidence.

The EPO provide a summary of the case law of the Boards of Appeal – this decision is cited in that summary here for implicit disclosure, and here for failure to consider evidence. It is also discussed in the CIPA Journal May 2015 for amendment based only on the drawings.

In this opposition appeal, Mewburn Ellis represented the patent proprietor, Napier Turbochargers Limited, against the opponent, ABB Turbo Systems AG, who appealed the decision of the opposition division to maintain Napier’s patent in amended form.

The appeal oral proceedings were focussed on three major issues, which are discussed in turn below.

Amendments based only on the drawings

The first issue was whether an amendment to claim 1 based only on the drawings adds subject matter contrary to Art. 123(2) EPC.

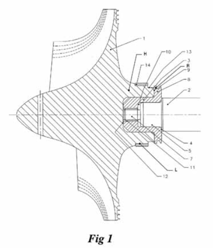

Claim 1 requires an impeller “mounted on a turbocharger shaft by means of an insert that is an interference fit in a blind hole of the impeller” (emphasis added). The blind hole was only disclosed in the drawings of the application as filed.

The opponent argued that the blind hole is only shown in a particular arrangement and context in the drawings and so its inclusion in isolation is an intermediate generalisation which unallowably adds subject-matter.

Mewburn Ellis, for the patent proprietor, successfully argued that the term “blind hole of the impeller” distinguishes the impeller type from a through hole impeller type, and was immediately derivable from the drawings, independent of other features shown but not claimed.

The Board of Appeal provided clarification as to when an amendment based only on the drawings is allowable; in addition to the usual requirement that the amendment must be directly and unambiguously derivable by the skilled person, when amendments concern features added from the drawings, the structure and function of the feature must be clearly, unmistakably and fully derivable from the drawings, as well as the fact they can be isolated from the other features.

The Board of Appeal considered that the skilled person, who is familiar with different types of impeller designs, will immediately recognize from the figures that these show blind hole type connections. This is further supported by the object of the invention in the patent as a whole to address the problem of “walking”, which only exists with a blind hole impeller. For these reasons, the Board of Appeal agreed with Mewburn Ellis that this feature was isolated from the other features shown in the drawings, and did not unallowably add subject-matter when introduced into claim 1.

Take home message:

Although it can be difficult, it is possible to successfully add a feature shown only in the drawings into a claim, without also claiming all the other features shown in the drawing. In order to do so, the structure and function of the feature, and the fact the feature can be isolated from the other features shown, must be clearly, unmistakably and fully derivable.

Implicit disclosure

The second issue was whether some of the features of claim 1 were implicitly disclosed in Document E1 – this would be the deciding factor in whether claim 1 lacked novelty over E1.

Claim 1 requires “a constraining ring comprising a material having greater strength and a lower coefficient of thermal expansion than the first material [of the impeller]”.

E1 did not explicitly state that the material of the constraining ring has a lower coefficient of thermal expansion than that of the impeller. The issue here was whether this was implicitly disclosed.

The opponent argued that by choosing appropriate materials for the constraining ring and impeller of E1, the impeller material implicitly has a greater coefficient of thermal expansion than that of the constraining ring.

Mewburn Ellis, for the patent proprietor, successfully argued that any material could be chosen for the constraining ring and the impeller, such that there is no implicit disclosure.

The Board of Appeal explained that as with explicit disclosures, the standard applied to implicit disclosures is the direct and unambiguous disclosure of a feature; i.e. a disclosure which any person skilled in the art would objectively consider as necessarily implied by the explicit content. Assuming that the skilled person would choose appropriate materials for the components, as suggested in the prior art cited in E1, does not mean that this would inevitably mean that the coefficient of thermal expansion of the constraining ring material would be less than that of the impeller material. Even though it might be typical for the skilled person to choose a constraining ring material with a higher coefficient of thermal expansion than that of the impeller, they would not inevitably make such a choice.

Take home message:

An implicit disclosure must be necessarily implied by the patent/patent application as a whole; the feature being a “typical” choice is not enough; the skilled person must inevitably make the choice of that feature. This is important not only in the assessment of novelty, but also in the assessment of “added subject-matter”, under Art. 123(2) EPC.

Failure to consider evidence

The third issue was whether a late-filed prior art document E12 should be admitted into the proceedings, and if not, whether that would be a violation of the opponent’s right to be heard by a failure to consider evidence.

The opponent only filed E12 with their grounds of appeal, not during the first instance opposition proceedings. E12 was therefore filed late.

It was thus, according to Art. 114(2) EPC, at the discretion of the Board of Appeal as to whether E12 would be admitted to the proceedings or disregarded.

The opponent argued that E12 should be admitted to the proceedings because it was filed in response to developments in the proceedings and because they considered E12 to disclose all the features of claim 1, and thus be novelty destroying.

In the oral proceedings, Mewburn Ellis were successful in arguing that E12 should not be admitted to the proceedings. This was because (i) no justification was originally provided for E12 in the grounds of appeal (justification was only given during the oral proceedings themselves); and (ii) E12’s significance over the other prior art documents already on file was not immediately apparent.

In response, the opponent submitted that the non-admission of E12 violated their right to be heard under Art. 113(1) EPC; i.e. that parties must have an opportunity to present their comments. In particular, the opponent argued that in view of their right to be heard, there should have been a “full discussion” of E12.

However, the Board of Appeal pointed out that if the opponent’s right to be heard did indeed mean a right to present all arguments as if E12 had been admitted to the proceedings, this would amount to E12 actually being admitted to the proceedings. This would imply that the Board of Appeal in fact had no discretion to disregard late-filed documents (contrary to Art. 114(2) EPC), and this could not be correct.

The Board concluded on this point that the parties’ right to be heard “is not absolute but must be balanced inter alia by the same need to procedural economy and due diligence that underpins Art. 114(2) EPC, which affords the board discretionary power to disregard evidence not submitted in due time”.

Take home message:

If new evidence (e.g. prior art documents) not seen in the first instance proceedings is to be filed for the first time at appeal, convincing reasons for filing that evidence late should be provided in the grounds of appeal. A party cannot rely on their right to be heard under Art. 113(1) EPC to get a full discussion of late filed evidence.

This is even more essential now that the new, stricter Rules of Procedure of the Board of Appeal have come into force.

Find the full decision here.

Our team has a wealth of experience and are trusted by some of the most successful companies on the global stage to handle their opposition cases. We prepare and deliver creative and persuasive submissions, helping to shape EPO practice. In this blog series we explore some of the decisions that stand out for us.

This blog was drafted by Lucy Coe.

Lucy is an Associate and Patent Attorney at Mewburn Ellis. She works primarily in the computer software, electrical engineering, transport, and mechanical engineering sectors. She is involved with all stages of the patent process, particularly in the drafting and prosecuting of applications in the UK and at the EPO. She also has experience in oppositions and opinion work. Lucy works with a wide range of clients in the UK, Europe, Japan, and the US. They include individuals, start-ups, UK-based SMEs, and multinational corporations. She has an MPhys (Hons) degree in physics from the University of Manchester.

Stephen is an experienced and successful patent professional with wide opposition experience. He has handled high value cases, multi-opponent cases, cases with parallel international litigation, and cases with substantial amounts of expert evidence. He is focused on obtaining the best outcomes for his clients, using his knowledge of opposition and appeal processes to provide helpful guidance and effective advocacy. His clients cover a diverse range of large, multinational and medium-sized companies in the UK, Japan and the US, as well as research institutes, universities and SMEs. He works primarily in engineering, materials and chemicals sectors, while specialising particularly in aeronautics, rail transport, power generation and medtech.

Email: stephen.gill@mewburn.com

-Dec-29-2025-09-11-25-2361-AM.png)